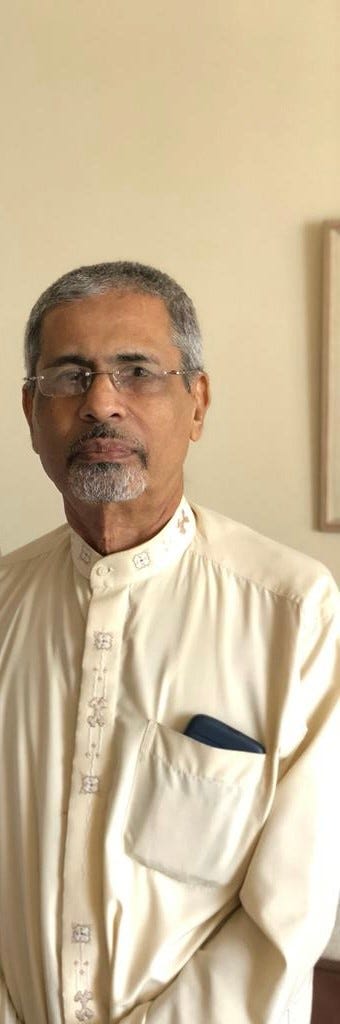

On the 20th of February 2023, my beloved father passed away after 4 days of being in the ICU following a sudden stroke. The nightmare that I had feared came to pass. I am not sure what is worse, dealing with a sudden death of a loved one or dealing with the inevitable death of someone who has been ill. Nevertheless, I have gone through many emotions grieving the loss of my father. From feeling overwhelmed, to intense emotions, to feeling like my childhood has suddenly disappeared, to feeling that I have to suddenly grow up. One month on, those emotions are still raw. All of this is normal I have been told, but it certainly isn’t easy, no matter what age you are to lose a parent and especially a father who has had a strong presence in your life.

My father was a man of deep faith and convictions and principles. He never compromised on this. Practically if you told him that you would call him or send him an email by a certain time, he would expect it. This was always a challenge growing up, when as a kid you learnt never to over promise and under deliver. But he made you value the concept of keeping your word and ensuring you helped people keep theirs.

He once wrote that “If you have to win the respect of people and live peacefully in this world, never consider yourself different from the rest and never expect special treatment from anyone”. This was how he lived his life not expecting any special treatment and not considering himself any different to anyone else. He went to great pains not to be an inconvenience to anyone, nor did he consider himself better than anyone because of his achievements. I never knew until recently about his ground breaking work in Nigeria or Ethiopia or the fact that he was one of the first PhD holders from the Eastern Province in Sri Lanka. He never chose to dwell on these accolades not because he didn’t value it, but because he feared that there would emerge an arrogance warranting special treatment because of it. He was very careful about arrogance and ego eating into the good deeds of someone. Many misunderstood this humility in him that meant that he didn’t show off his achievements and was always happy to not be in the limelight preferring to shine the light on others. At a time when people vacuously elucidate more than they have actually achieved, it was strange to many that my dad didn’t cave into societal demands or sang his own praises or that of his family. “Who are we trying to impress?” would always be his response when I would clash many times with him on this because the narcissist in me thought I had to talk about my achievements. His quiet diplomacy taught me a great leadership principle that when you shine the light on someone else, inevitable some of that light falls back on you.

My dad was simple, again a quality that was largely misunderstood. In a world of bigger, better and shinier brands, he was an island in continuing to simply advocate that success is not about the bank balance or the car you drive but the brain talent you possess and the value you bring to people around you. He would tell me “why do you need to drive a $200,000 car or wear a $1000 wristwatch when you can drive a $10,000 car or wear a $50 wristwatch? They both have a functionality and a purpose. It’s not making you more efficient to have the more expensive product. You can save that and use that to help someone”. He lived that mantra as he truly believed that if you can make a difference in someone’s life, then you are a rich person. Judging from the number of people who have contacted our family following his passing saying how he helped them, my father was indeed a very wealthy man, touching the lives of all those he met with a compassion that I have not seen and having countless of voiceless people praying for him and sending him their thanks. From security guards from neighbouring houses, to trishaw drivers to academics, political leaders, faith leaders, leaders of industry, all came to pay tribute to him saying how he had helped them or advised them or touched their lives. There is a concept within Islam of giving in charity with your right hand so that your left hand doesn’t know. Certainly, dad gave in charity that we did not know about. Even recently we have been getting messages from different parts of the country of the level of his generosity. There are at least 3 or 4 Dr Saleems in Nigeria, kids who were named after my father, after their fathers worked for our family and the gratitude that they had for him and the greatest honour they could bestow in naming their kids after him. Someone in their condolence message to me said he dined with kings and walked with the poorest of the poor and there was no difference in how he treated them. This is the best description someone can give about my father.

He was a self confessed “Ghandian”, espousing subsidiarity, power from the bottom up as key to bringing about societal change. He truly believed that you had to model that change you asked people to aspire towards, and you could see him modelling this through his behaviour, diet and his relationships with others. He would tell me “Don’t ask people to sacrifice or volunteer something if you are not prepared to sacrifice it or volunteer yourself”, and sacrifice he did, whether it was his time or his money for a cause greater than himself.

He was also a quiet man, with very few words, but always reflecting and thinking, and asking the right question at the right time. He mastered the art of asking the right question and I have seen people who are experts flummoxed by his curve ball questions asking them to think about something they had not thought about. I remember him asking someone from Transparency International how transparent they were, when they came to pitch to a charity he was involved in about their services.

One of his philosophies in life was that he never wanted to be a burden on anyone or to cause inconvenience. Conflict was not his style, preferring to not engage or being a true preponderant of the Third Alternative, seeking creative solutions to problems. “Everything has a solution that could be overcome”- It’s something that I truly try to model in my own life, not to think within the box but to think there is no box.

He chose the mantra that “I will speak only when I have something useful to contribute”. Yet his quietness had a strength of character and purpose which is evident by the glaring hole and silence we feel in our lives and the home in Colombo, such was the strength of his character.

Next to being a deeply spiritual person, his second religion (as one of his school friends told me) was love. The love and compassion of people, friends, and of family. He was proud of his roots and his influences both in Sri Lanka, UK, Nigeria, Ethiopia. He was proud of his Commonwealth Scholarship that enabled him to do his PhD at the University of Ibadan, where he formed close ties with his supervisor from India. Even today, the ties with that supevisor’s (who has sadly passed) family are strong. He was proud of being an old boy of Jaffna College, understanding cultural diversity and inclusion in a way that was not understood then but has now become an industry within the international development sector. For him diversity was a positive disruption bringing different ideas and perspectives to the table. That pride and experience he carried with him even to his death and evident from all those who came to mourn him. Even a week before he passed away he had participated in an old boys association meeting. Conspicuous by their presence at his funeral and the days and month that has passed has been his classmates from over 50 years ago, who still remember “Saleem” as he was known, for his mischief, but more importantly for his appreciation of the other and respect for human dignity. Despite being spread across time and space, these relationships and memories are testimony to someone who truly understood and embraced diversity.

He was a proud Sri Lankan always discussing the potential of what the country could be, blessed in its diversity and open to the concept that the country belongs to all, he pushed for greater equity and equality at all levels of society and would write about it endlessly in a number of different columns. He emphasised that all of us have a role to play to contribute because the country belonged to all of us, not to a certain race or faith. This was what he had learnt from school and his friends and time abroad and is something that he truly felt Sri Lanka as a melting pot of faith and culture could aspire to. Even to his final days, he was thinking and writing about how we can work on improving Sri Lanka. One of his conversations with me was lamenting about how sad he was about the number of people wanting to leave Sri Lanka for pastures new. He wasn’t against people leaving the country but he also felt that after having spent more thatn 32 years abroad, there was no place like home, and that it was only Sri Lanka’s loss that bright people were leaving.

For him the concept of family and home was perhaps the third religion. Having been sent to boarding school at the age of 8, he was always keen not to lose out on the notion of the family. It was a conviction that centred him throughout his life and something that I grew up strongly believing in. When I was younger, after having watched the Godfather movies, I used to joke with him saying that our family seemed to be like the mafia because family was everything. However it was something that he strongly believed in. A year after he got married, my maternal grandfather passed away from cancer leaving a very young family to care for. My father took it upon himself to become the second father of my mother’s family. In later life, he would become a fatherly figure to the families of his siblings. My father would later tell me that this experience disciplined him and made him realise the importance of responsibility. It is this sense of responsibility for family that made him take early retirement in 2001 and move back to Sri Lanka allowing my mother to come back and spend time with her mother. When the tsunami struck Sri Lanka in 2004 affecting our immediate family, it is that sense of responsibility that allowed him to take a lead in the role of the recovery process for the larger extended family, ensuring the sub family units to return to their homes once the water levels receded. The post tsunami period from housing to coordinating support and recovery were done in the spirit of preserving family cohesion and common interest. My father when he retired in 2001, said that he wanted to spend more time looking after my mother, which in the last 6 months of his life, he did when my mother fractured her arm and needed support. The pleasure he took to look after her was evident in how he spoke of being blessed by God to be able to look after mum in a way she had done for him for the last 53 years. He was discovering the joys of being a grandfather to 4 grandkids and interacting in a way perhaps that he had not done previously with my sister and I. I would joke that he was having to do the things with his grandkids that he didn’t have time to do with his kids. He simply enjoyed this new role and talked about how blessed he was to have that new responsibility. Family was extremely important for my father. When I was getting married, he would tell me that it is not just an extra person coming into our family but her entire family as well. Family bonds were essential and sacrosant to him and it pained him when there were strains and tensions. In his true way though where there was conflict, he never wanted to take sides but would try and mediate. He would not know it but in his death, his dream of a united extended family has come true with family from his side, my mom’s side and my in-laws coming together, pitching in and working together. It’s one of the times that I miss that I can not share that anecdote with him, knowing how happy he would be to see people working together. More than anything he was always so proud to see the next generation standing up and developing their own lives. In death, I learned what my father had always tried to teach me about the importance of that extended network of family, who rally round and often sacrifice themselves to support you at times of great need.

He would teach me that taking responsibility is important in whatever needs to be done, and understanding your ability to respond to a situation. This is definitely one of the key lessons that I have taken in my life in whatever I do. This meant doing what you could do and being the best about it.

My dad was a deeply practicing Muslim, proud of his faith. My enduring memory of him is always murmuring some prayers whenever he could. He never missed his compulsory and supplementary prayers and fasts, nor the recitation of the Quran. Unwavering on compromising his faith, he also sought to delve deep into the meaning of faith. He was not content just to blindly follow but to question, to seek, to dig deep and understand. I understand and inherited his love of reading, digging into the theology, spirituality, understanding different Islamic movements, politics and intricacy of the Islamic faith. Spiritual practice was something he really sought to inculcate in his life and something he shared with me. The importance of that discipline of doing small practices regularly every day and not focussing on trying to do big things, but also the sense that anything that you do can be turned into a sense of worship. I would often complain about the mundane and regular things in life and he would respond “these are just opportunities to show your gratitude to the Almighty and also an opportunity to correct yourself on a regular basis”; so that regular commute turned into a journey of reflection and pondering and asking “Is there something I can do today that I didn’t do yesterday? Is there something I can do to make today better than yesterday to correct any mistake that I made?”

He was someone who cared deeply about the ethics and behaviour of Muslims beyond just adherence to articles of faith. For him, adherence to worship had to give Muslims an edge in terms of their behaviour with each other, their character and the values. If this was not the case, then mere observance of prayer or fasting would not suffice. He was often distressed with the state of the global Muslim community and in particular the state of affairs of the Sri Lankan Muslim community. He would not hesitate to tell off academics, religious leaders or politicians if he thought they did something wrong. He would talk for hours about how he felt that Muslims had departed from their spiritual purposes and focussed more on form not spirit. He would say that there are a lot of Muslims nowadays but there is very little Islam, very little development in the internal spirit of Muslims who he felt focussed more on outward manifestations of piety. His analysis was based on the fact that the behaviour, attitudes and values displayed by Muslims were often at odds with the teachings, practices of Islam whilst he felt they focussed more on dress code and food. His thinking around Islam and Muslims often put him at odds with the mainstream Muslim intelligentsia, but endeared him to many others. He was credited by a Buddhist monk for helping said monk change his negative perceptions of Muslims. His approach to understanding Islam and its purpose in the world is the foundation of how I approach my interpretation of the faith, the teachings and the practices.

He also laid great emphasis on interfaith dialogue and the role of faith leaders. He saw the latter not just as teachers of prayer but more as instruments of ethics and values. His vision was that religious leaders should have a greater role to play to combat and denounce racism, discrimination and any threats to human dignity. He called faith leaders the conscience of society and called on them to rise to the challenge of valuing human dignity. In recent years, he focused on spirituality as transcending religion and rising above ideological affiliations, being the glue that binds people together in a spirit of ethics, morals and basic humanity. He understood the need for a common space and substance from which can emerge a shared vision to trigger action for the unity of humanity underpinned by compassion. Idealistic yes, but totally aspirational, which has prompted a Christian priest to say that “Dr Saleem was not a religious leader but a leader of religions”

My experience with my father I can surmise, was in three phases. The first phase was as a son who enjoyed life with his father. Between our time in Nigeria and Ethiopia, I have fond memories of a fun loving father who loved horse riding playing tennis, organising birthday parties and going on holidays.

I rarely knew of his professional background but I knew he travelled around a lot because of work but it meant more toys for me. I never knew of his work but in recent years have come to realise his intellectual impact especially when Academia.Edu tags me on papers that reference his work and writings still to date and asks me if I that “Dr M A Mohamed Saleem”? Someone called him the “father of the fodder banks” but in true reflection to my dad’s character he underplayed this achievement. Yet his ties with his ex colleagues from Nigeria and Ethiopia are as strong now as they were then and have transcended generations with myself working and engaging with a number of them.

The second phase was when I went to boarding school and then university back in the UK at the age of 16. I know my father was reluctant to send me based on his experiences at boarding school, but made it a point to try and visit every quarter as he transited in London on every official trips that he made. it meant that my friends and i got treated for fancy dinners which when you are a struggling uni student meant quite a bit. During this time, it was a learning time for me, understanding how to see the world and to take decisions on what to do or not do. I may not have fully followed through in my learnings, but this time of spending together allowed me to focus on my career as an engineer and then to diversify. I still value that time that he took to come and spend even a day with me during his official trips. More importantly I valued the supply of food that he would bring from my mother.

The third phase was after the tsunami in 2004, when I came back to work with Muslim Aid in Sri Lanka’s post tsunami recovery and I had the privilege of working with my father on different projects.At that time, my father had developed a keen interest in understanding the ghandian philosophy and working on alternative energy and medicine, along side his interfaith work. This was the synergy that allowed us to come together to work on something better. Though we sometimes had professional differences on how to approach things, we always resolved it in a way to learn from each other. It remains my greatest pleasure and honour to have worked alongside him on a number of different projects along the years from the Commonwealth People’s Forum to a number of peace conferences to humanitarian relief to engaging with faith leaders. I would also have a stint at working with him again when I came back to work in Sri Lanka from 2013–2017 and though it was a different platform, the aim was the same. How can we best unearth the potential of Sri Lanka? more improtantly what was the role of faith leaders and faith communities? The time that we worked together was the most valuable university lesson that I have followed. it is these lessons that I carry with me when I deal with people or situations.

He was not only my father but my mentor and professional confidante. When I had issues at work I would talk to him about the frustrations of not being valued, and he would always remind me that the value is in the work being done and the impact being felt on the ground and being seen in the eyes of God. “Don’t worry about these temporary accolades and appreciation so long as He knows what you are doing” was his constant reminder as he sought to temper my urge for more. Accolades only serve to make you forget who you are was his response.

One of my last conversations with him was around legacy and my worry about what mine would be. His answer was typically that “those whose legacies posterity talk about and idolize never, in their lifetime, were concerned about their own legacies. They lived a life of conviction and realization that they had a purpose and pursued it regardless of their own challenges and changing circumstances. Only when such people depart from the stage others who had been around or who came after them built up legacies for the departed. Those who were deeply concerned and conscious about their legacies invariably were also found to live double lives and exhibited split personalities. This is because such people tended to tailor their actions to cater a targeted and selected group(s). We can see this happening more in this contemporary world. Such legacies have no value either to the one who worked hard to accumulate them or to those who succeeded that person as siblings, or associates. after the person’s departure. Such legacies may not even have any value and may even be discounted in the final assessment. One requires no fancy education or material resources to build this legacy. It requires only the realization that every human is to function as a humble servant and he is required to be the vicegerent of the owner for the beginning and the end. It does not matter what means of livelihood the person adopts.”

He was my editor for numerous pieces of my academic writings and especially during my PhD phase, read through my thesis at least twice to ensure that it made sense. In fact, the last piece of work that he helped to edit was a chapter I wrote around Muslim Democrats in Sri Lanka for the book ‘Rethinking Islamism beyond Jihadi violence’. In his typical thoughtful way, he cautioned me to reconsider whether people might misinterpret what I was trying to say and asked me to reframe the points being made. “We can’t conflate islamism with jihadi violence but its also important you stress the true nature of Islam” is what he told me.

When I got my PhD in 2019, I joked with him, we now have a Dr M A Mohamed Saleem, number 2, to which he replied “I have to retire now”. But typically that was my dad, his next response was, “what are you going to do about it now?” His philosophy was that you just do the best you can in what you can do. Be the best. If you are a street cleaner, be the best. If you are the scientist be the best. Never rest on your laurels, continue to work and push the boundaries.

Little did I realise that 4 years after, this retirement would be permanent and suddenly that anchor and compass would no longer be there. In his book “Who will cry when you die?”, Robin Sharma talks about tapping into that special ability to make the world a better place. My father had this special ability to connect with someone, make them feel important, special and unique, to understand their problem and come up with a way of helping them. The 11th century persian scholar Abu Sa’id Abul-Khair said (and this was taken up by Ralph Waldo Emerson amongst others) that “When you were born you were crying and everyone else was smiling. Live your life so at the end, you are the one who is smiling and everyone else is crying.”

My dad would certainly have been embarrassed at all the accolades that are being thrown his way, in the wake of his passing and by all the people who have emerged from the woodworks to pay him tribute. He would probably be angry with me for writing this because he was one to stay in the shadows. I hope that he is smiling because his life was full and that his legacy is a continuous charity which all of us will strive to emulate and keep going and that he forgives me for wanting to share his story and example with the world as a way to inspire, to remember and to celebrate him.

Whilst my father in his quiet way achieved a lot for the community, he was first and foremost my father, and I will truly miss him.

May God bless him, and accept him into His highest fold. May we be united in a better abode.