Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is tragically widespread along migration journeys, especially when these take place along irregular routes “due to armed conflict-related poverty, insecurity, and distress.” Risks of SGBV – including those related to trafficking and modern slavery – can increase in countries of transit and destination.

In this post, Sandra Pertek, Ahmed Al-Dawoody, and Amjad Saleem highlight the critical importance and role of faith leaders and communities in tackling SGBV, discussing the importance of incorporating faith literacy and sensitivity in SGBV prevention and responses, and calling for an increased engagement of humanitarian actors with faith actors to address SGBV in armed conflict and migration.

While undisputedly prevalent, the exact numbers of migrants[1] experiencing sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) are unknown and vary depending on context. Available data confirms that women and girls are disproportionally affected, with the World Health Organization estimating that one in three women and girls will experience SGBV during her lifetime, yet men and boys are also affected by and vulnerable to SGBV, including as a form of torture and in situations of trafficking. One study from the Netherlands and Belgium reported that up to 69.3% of female and 28.6% of male migrants had been subjected to sexual violence after they arrived in Europe.

Some migrants may have already been subjected to sexual and gender-based violence prior to leaving home, as is often the case for those fleeing armed conflict, violence, or other serious harm. For them, the risk or reality of SGBV along the journey can therefore compound the trauma already experienced in their country of origin. Other migrants find themselves stranded in areas experiencing armed conflict or violence, or deprived of liberty for immigration-related reasons, finding themselves at a higher risk of experiencing SGBV.

Gender inequality[2], harmful social norms and practices, and discriminatory views on women or gender roles in society underpin the perpetration of SGBV worldwide. In addition, multiple factors can further increase the risk of SGBV for migrants – from loss of family and social connections, economic deprivation, and social exclusion, to legal protection gaps, mental health issues, and lack of language skills.

Intersecting identity-based inequalities, such as religious or ethnic discrimination, racism, and sexism, can also drive the perpetration of SGBV, and many forms of SGBV are simultaneously sexist and racist. Conflict-related sexual violence may have strategic and tactical motivations, take advantage of the situational and contextual vulnerabilities of migrants (including by aid workers), or it may be tolerated by a culture of impunity.[3]

Religion and humanitarian action: a leap of faith

Faith and religious adherence remain part of the lived experience of many communities around the world. Subsequently, many migrants maintain a religious affiliation. For many, religion (faith and/or spirituality) also remains a part of their migration experience and an important symbol of connection with the past and their places of heritage. With the loss of resources and in under-resourced settings, religion – meaning religious beliefs, traditions, practices, organization and experience, and religious leaders – becomes a resource from which to draw strength and comfort and to find a sense of belonging. Dangerous sea and desert crossings, unimaginable living conditions and near-death experiences can lead to an increase of faith among migrant survivors of sexual and gender-based violence, who find meaning and build resilience in the face of abuse, relying on prayers, religious scriptures and religious rituals.

Religion, therefore, can operate as a protective factor, yet it can also manifest as a risk. Religious discrimination and persecution, or cultural practices and understandings, can contribute to the perpetration and exacerbation of SGBV, especially towards minority groups. Some patriarchal religious interpretations are also misused to centralize power, control resources, and limit women’s participation to impose certain (dis)orders.

Beyond listing the benefits and ill effects, however, one must remember: religion itself does not have agency! It is interpreted and enacted by social actors and intersects with culture, power, access to resources, and politics, to name a few. It is, therefore, important to consider the ways in which humanitarian actors can work with faith-based actors to tackle SGBV that is condoned or indirectly promoted by religious ideas and teachings.

Various organizations already work with religion to address sexual and gender-based violence. One comprehensive framework is “Faith for Rights”, comprised of the 18 commitments adopted in Beirut in 2017 by faith-based actors and human rights experts, and offering a robust tool and peer-to-peer learning methodology for engaging with religious leaders.

Several of the “Faith for Rights” commitments are directly relevant to leveraging religious values in support of international humanitarian law (IHL), human rights, and refugee law, as applicable, including in combating SGBV in migration contexts. As religions are necessarily subject to human interpretations, commitment III pledges “to promote constructive engagement on the understanding of religious texts.” Commitment V very squarely addresses SGBV by pledging to revisit “those religious understandings and interpretations that appear to perpetuate gender inequality and harmful stereotypes or even condone gender-based violence.” This international instrument, arguably soft law, not only quotes general comments by UN treaty bodies[4] but also several religious sources, including two Qur’anic verses.

The related #Faith4Rights toolkit contains renewable sources of practices and knowledge emanating from different religions and regions. For example, Christian and Muslim religious leaders of Cyprus stressed that “[v]iolence against women and girls, in whatever form, is a contradiction to the will of God and unacceptable…We strongly believe that religious leaders don’t only have a responsibility but also a religious duty to stand united against violence in all its forms everywhere, including violence against women and girls.”

Humanitarian actors with limited religious sensitivity and faith literacy and who are disengaged from contextual religious dynamics may be insufficiently equipped to deal with the impacts of monopolized religious interpretations on the perpetration of violence and exploitation of women and marginalized groups. Innovative and faith-sensitive approaches, as well as greater faith literacy, are needed to prevent, respond to, and mitigate SGBV occurrences along migration routes – and to ensure adequate transposition of standards and evidence-backed approaches to supporting survivors.

Working with religion to address SGBV in migration settings

Disregarding the faith of crises-affected communities disrespects the lived experiences of millions of people, denying their agency, representation, thinking, and ultimately their power. Working with religion as a cross-cutting factor – a multiplier of resilience and risks with indirect and direct effects – in SGBV prevention, risk mitigation, and response can be useful at multiple levels. Faith communities (groups of congregational members affiliated with a certain religion, including institutions and leaders) are often key players in humanitarian action who are well-equipped with local knowledge to address specific community problems. Faith actors, including faith communities and faith-based organizations, have traditionally demonstrated that small initiatives that respond to local needs and build local partnerships can contribute to global changes.

A faith-sensitive approach in migration contexts could mean deploying religious resources to support migrants in their trajectories. For example, faith communities can play an important role by helping to connect migrants to trusted local faith communities to access support along migration routes. They can compensate for the social disconnections and loss of social networks that migration often creates. Faith-based groups can also be present across migratory routes to ease the lengthy and dangerous journeys, providing immediate assistance and emotional support, as does the inter-faith network A World of Neighbours. Faith communities also play an essential role in helping migrants integrate into local communities by finding community support in new environments. They enable migrants to develop social connections and practical support to settle down and rebuild their lives.

It is important to note, however, that faith communities are not a panacea – they can also be the root of misunderstandings, disagreements, or different interpretations of religious and humanitarian principles. Many faith communities, regardless of their size, have a history of strife and struggle, on one hand, and of cooperation and collaboration on the other.

It is against this backdrop that we ask questions such as: how can personal and communal religious resources – beliefs, practices, experience, and organization – be leveraged in tackling SGBV along the migration journey? Can humanitarian workers engage with religious teachings and motivations of faith-based actors to mobilize the protection of survivors of sexual and gender-based violence? What is the role of religious leaders in SGBV prevention and response in humanitarian crises, and how they can better engage with humanitarian stakeholders?

Towards understanding and addressing SGBV in Muslim contexts

When dealing with faith actors, among others, all sources of influence, be it religious teachings, cultural norms, local beliefs, and traditions, must be utilized to mobilize protection against SGBV. Even when monopolized religious interpretations are used to justify the perpetration of sexual violence and exploitation of women, it is still important to engage in dialogue on such interpretations to enable clarify and better understanding of the causes of violence and develop protection, response, and prevention mechanisms relevant to the local context.

For example, as a significant number of armed conflicts are taking place today in Muslim-majority countries, and that Islamic law plays a vital role in the daily lives of hundreds of millions of Muslims globally, the influence of Islamic law cannot be ignored in developing SGBV protection and prevention approaches in Muslim settings.

International humanitarian law strictly prohibits sexual violence, both in IHL treaty norms[5] and customary law[6]. Similarly, under Islamic law, rape and other acts of sexual violence accompanied by the use of force falls under the crime of ḥirābah (terrorism).[7] The twelfth-century Andalusian Mālikī judge Abu Bakr ibn al-‛Arabī (d. 1148) relates that he punished a group of highway robbers who abducted a woman and raped her. This strict Islamic legalistic approach prohibiting SGBV may one, enhance acceptance, respect, and universalization of relevant international legal frameworks; two, serve as a severe deterrence in relevant contexts; and three, provide a local accountability framework when relevant international legal frameworks are rejected by certain non-state armed groups.

A faith-sensitive approach is also necessary to accommodate any religious needs of survivors of SGBV, to deal with treatment and referrals, and to mitigate psychological, physical, and social trauma. Many people resort to their faith, religious leaders, and places of worship to protect and empower themselves in times of painful and traumatic experiences. Islamic institutions and Islamic religious leaders are no exception here and can be more involved in developing SGBV responses in Muslim contexts to support the healing of survivors.

However, working with SGBV survivors requires personnel trained in SGBV, in addition to more general psychosocial support qualifications. Sadly, many religious leaders are not trained to handle the specific needs of a person following an incident of SGBV. Religious leaders and scholars specifically trained to handle SGBV cases, especially women, along with the more secular practitioners of psychosocial support and case workers, should be collectively included in developing SGBV responses, not only because of their influence on their communities, their awareness, and sensitivity of the issue but also because their role can be irreplaceable to ensure a gender and trauma-sensitive response, including medical, psychosocial and psychological care and support.

Elena Fiddian-Qasmiyeh argues that “Muslim women particularly have often been overlooked as agents of change by international organizations because they do not appear to conform to a Western notion of empowered women when they wear the hijab or niqab.” Yet, there is a range of religio-cultural assets that are a lifeline for Muslim survivors in crises, through which women ground their agency and belonging. For example, women’s communities and faith groups (e.g. halaqa) are important allies in working with women survivors to raise their self-esteem and awareness of their religious socio-economic rights, including protection and empowerment, as enshrined in the religious teachings. Survivors can also benefit from spending time with other people in similar situations, to share their concerns and offer mutual emotional and practical support. Exchanging stories and viewpoints in peer groups can foster healing, too.

In other words, a trauma-informed response should necessarily include a diversity of expertise, including religious leaders who are well-equipped and trained to provide a survivor-centered response. Religious leaders working with SGBV survivors should be also informed about any unintended negative consequences that mandatory reporting might entail, and guided to ensure a survivor-centered approach is followed throughout their interactions.

In particular, it is important that any stigma – including that towards men, boys, and minority groups might face when disclosing and seeking support – is adequately addressed by religious leaders in their faith communities. Similarly, humanitarian, development, and peace-building actors focusing on SGBV could consider how to work with men and boys by drawing on their religious resources (for example ideas of human dignity and practices such as honouring women) in a group setup to promote healthy masculinities and family power dynamics.

There are opportunities for creative engagement with men and boys in humanitarian settings, from meaningful consultations to mobilizing commitments, for example, tackling topics suggested by men directly as entry points, talking about men’s sexual health, stigma awareness workshops, and creating networks to assist with referral pathways.[8] For instance, religious institutions and religious leaders can be involved in developing anti-SGBV communication messages and dissemination methods through religious congregations, such as during religious sermons and informal gatherings, as well as published material by influential religious leaders. Faith leaders, often enjoying authority, trust, and access in their communities,[9] can also help to translate and understand the humanitarian principles through a language of faith to tackle sensitive issues, such as SGBV. They may sometimes be the primary entry point for disclosure and for guidance and referral for survivors of sexual violence. Places of worship can also be supported with capacity building to become safe places for survivors of SGBV across settings.

Certain interpretations of religious principles enshrined in domestic law pose barriers to survivors of sexual violence seeking access to justice or care. In such cases, religious leaders and states should consider how these laws can be reformed to better support – and reduce the stigmatization of – survivors of sexual violence. International law and standards should be referenced to guide this process.

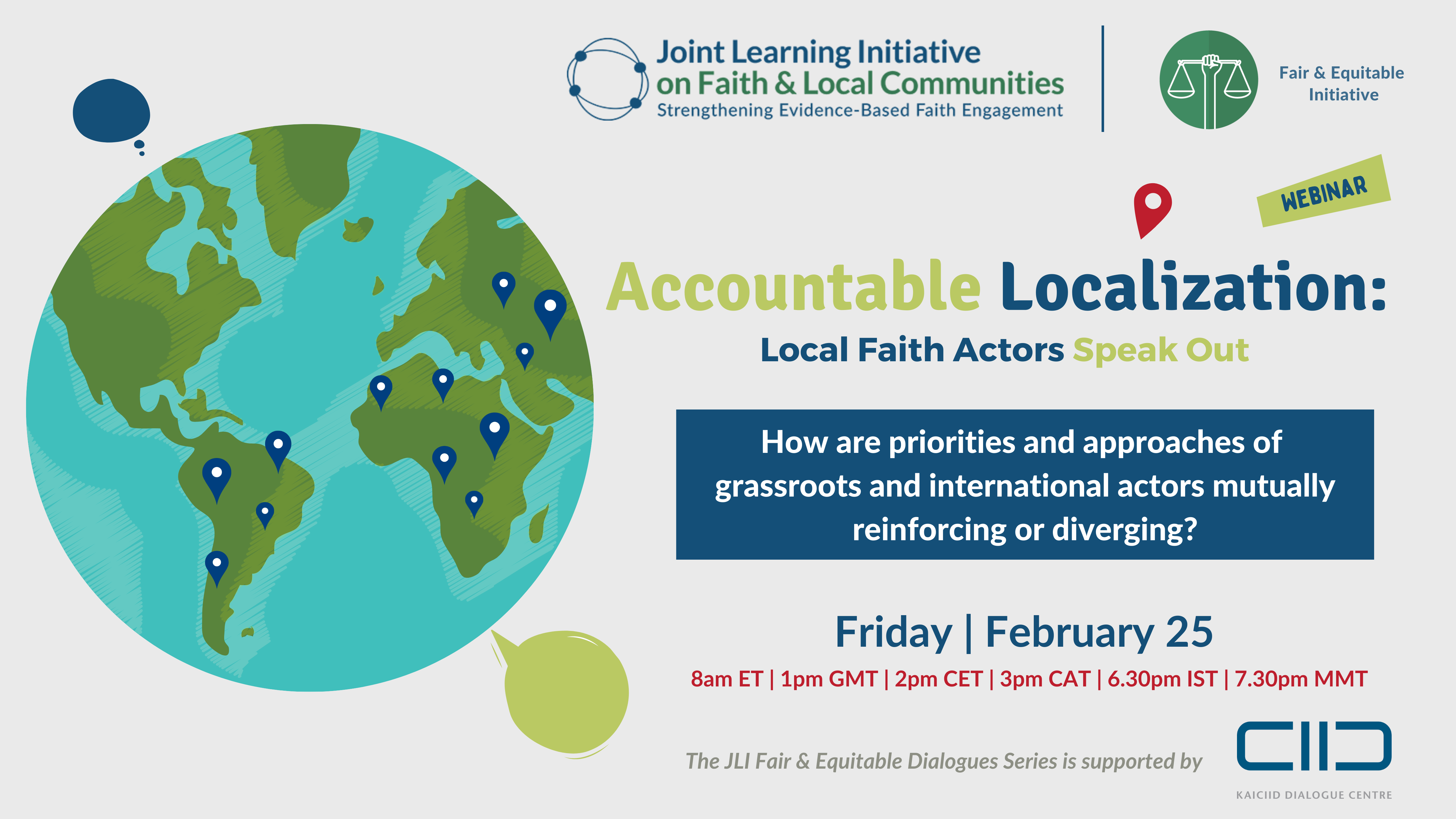

Therefore, humanitarian actors should engage more with faith-based actors, to raise the religious literacy of the former whilst improving the understanding of the latter around humanitarian action and principles. This has been a rallying call from the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit and the work done by organizations such as the Joint Learning Initiative on Faith and Local Communities, to strengthen the engagement of faith actors in the achievement of humanitarian goals. Similarly, UN Security Council 2467 (2019), in operative paragraph 16(c), highlights the importance of engaging with religious and traditional leaders to advocate against sexual violence in armed conflict and support the reintegration of survivors and their families.[10]

By increasing this engagement and mutual understanding, there is an opportunity to raise the awareness of religious actors to the reality of SGBV in their contexts and the vulnerability factors to SGBV in order to tailor communication messages, training and expert workshops as well as dissemination methods that are context-specific and more impactful.[11] Both state-affiliated and independent religious institutions and individuals have huge outreach and influence through their traditional and modern channels of communication. The traumatic experiences of SGBV necessitate a multidisciplinary, innovative, context-specific, and gender- and faith-sensitive protection and prevention response. Hence, the particularities of the very single case and situation of SGBV must be addressed accordingly. Inadequate, simplified, and romanticized responses do not contribute to tackling the continuum of SGBV along migratory routes, from countries of origin through countries of transit to countries of destination.

Seeking solutions to SGBV: Islamic philanthropy

In addition to drawing support from religious texts, Islamic social financing can be a useful tool for working with survivors of SGBV. Throughout Islamic history, the three main Islamic financial instruments – zakat (compulsory alms giving), ṣadaqah (optional charity) and waqf (endowments, trusts) – have contributed considerably to meeting individual and community needs. These instruments have focused on alleviating poverty and suffering of beneficiaries and meeting mainly, but not exclusively, the humanitarian social, educational and medical needs of the community. Moreover, they aim to empower the beneficiaries.

Although these Islamic financial instruments have “the potential to ease the suffering of [hundreds of] millions around the world,” their use “in the non-faith-based humanitarian sector is a relatively new issue for both international organizations and Muslim jurists.” A 2016 report by the Global Humanitarian Assistance Program explored the role of Islamic social finance, especially zakat, in humanitarian funding. Here, what matters is not the amount of money to be collected, but what is done with it. There is an increasing realization that there is a lack of understanding as to how to apply the various instruments of Islamic social financing.

For example, zakat has eight categories of recipients, which have not yet been properly examined, to understand supporting non-Muslims. Among these are the levying of administration costs for the collection of zakat, vital infrastructure projects, peacebuilding, and initiatives combatting human trafficking. All of these remain grossly underfunded and unexplored by zakat.

It is worth referring here to the UNHCR’s “Refugee Zakat Fund”, whereby at the time of writing 14,030 people had donated their zakat in 2023 and 4,557 refugee and internally displaced families had been reached in 2023. Such innovative platforms mainly facilitate the provision of much-needed funds and services to those who need them.

It is not possible to assess exactly the amount of the annual spending of zakat. However, its annual potential size was estimated “between 200 billion and one trillion US dollars, according to Obaidullah and Shirazi in 2015 and the World Bank and IDBG in 2016.” Therefore, zakat, ṣadaqah, and waqf can all make a considerable contribution to supporting the specific needs of survivors of SGBV and the financial needs necessary to develop short- and long-term SGBV protection and prevention responses in Muslim migration contexts. More work needs to be done around developing standards around the financing of protection and prevention responses.

Conclusion

We need to rethink how to engage with faith leaders and institutions in SGBV prevention and response along the migration trajectory. Secular actors should not dismiss the fact that faith is often a lived experience of migrants and can become a source of comfort during times of trauma. We also need improved literacy and sensitivity on addressing misinterpretations of religious perspectives. SGBV and other human rights violations in the name of religion highlight the importance of humanitarian actors engaging with religious leaders using a ‘Faith for Rights’ approach and toolkit, and religious leaders can benefit from the same toolkit to leverage their moral weight in the service of humanitarian values.

From a religious perspective, we need to unite religious and secular scholars to develop a protection framework that incorporates religion as both a challenge and a solution. In addition, there is a need to better understand the role of Islamic social financing, and how it can set in place new norms for the protection of people facing humanitarian challenges.

These are the necessary steps towards, inter alia, fulfilling Strategic Objective 3 of the ICRC Strategy on Sexual Violence 2018-2022 which “aim[s] to influence actors at national, regional and international level to create a legal and policy environment, in which sexual violence is absolutely prohibited (and not tolerated), and to ensure that victims’/survivors’ dignity and needs are at the center, with their agency recognized and respected.”

[1] This post uses the broad description of migrants adopted by the International Red Cross Red Crescent Movement (the Movement), which, for the purpose of the Movement’s humanitarian response, considers as migrants all persons who leave or flee their country of origin or habitual residence to seek safety or better prospects abroad, and who may be in distress and need protection or humanitarian assistance. This includes migrant workers, migrants deemed irregular by public authorities, people displaced across international borders by armed conflict or violence, but also refugees and asylum-seekers, who are entitled to specific legal protection under international law. This inclusive description, focused on needs and vulnerabilities, reflects the Movement’s operational practice and emphasizes that all migrants are protected under several bodies of law.

[2] Gender inequality as a root cause is identified for example in UN Security Council Resolution 2467 (2019): “…exacerbated by discrimination against women and girls and by the under-representation of women in decision-making and leadership roles, the impact of discriminatory laws, the gender biased enforcement and application of existing laws, harmful social norms and practices, structural inequalities, and discriminatory views on women or gender roles in society”.

[3] Elisabeth Jean Wood identified three broad categories of motivations for conflict-related sexual violence: 1) strategic (carried out to achieve the organization’s objectives), 2) opportunistic (for private reasons), and 3) tolerated practice (because of culture of impunity or lack of willingness to tackle it for a number of reasons. See Elisabeth Jean Wood, “Conflict-related sexual violence and the policy implications of recent research,” International Review of the Red Cross, (2014), 96 (894), pp. 470-474. https://international-review.icrc.org/sites/default/files/irrc-894-wood.pdf

[4] Joint general recommendation No. 31 of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women/general comment No. 18 of the Committee on the Rights of the Child on harmful practices, CEDAW/C/GC/31-CRC/C/GC/18, para. 70.

[5] For example and among others, via Article 3 common the Geneva Conventions, as well as Art. 12, GC I, Art. 12, GC 11, Arts 13 and 14, GC III, Art. 27(2), GC IV, Art. 75(2)(b), AP I, Art. 76(1), AP I, Art. 77(1).

[6] Rule 93 of the International Committee of the Red Cross’s study on customary IHL.

[7] Ahmed Al-Dawoody, The Islamic Law of War: Justifications and Regulations (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), p. 274.

[8] ICRC (2022) Male Perceptions of Sexual Violence in South Sudan and the Central African Republic https://shop.icrc.org/male-perceptions-of-sexual-violence-in-south-sudan-and-the-central-african-republic-pdf-en.html

[9] See, for example, https://shop.icrc.org/male-perceptions-of-sexual-violence-in-south-sudan-and-the-central-african-republic-print-en.html

[10] UN Security Council 2467 (2019), operative paragraph 16. c, states: “Encourages leaders at the national and local level, including community, religious and traditional leaders, as appropriate and where they exist, to play a more active role in advocating within communities against sexual violence in conflict to avoid marginalization and stigmatization of survivors and their families, as well as, to assist with their social and economic reintegration and that of their children, and to address impunity for these crimes.“

[11] See, for example: EC (2021) Engaging with Religious Actors on Gender Inequality and Gender-based Violence. Compilation of Practices. https://www.abaadmena.org/wp-content/uploads/documents/ebook.1636550388.pdf.

this originally appeared here